FAST FACTS

• The Pirates were the city’s first NHL team.

• New York Americans’ Billy Burch, the reigning MVP, scored the first NHL goal in the city of Pittsburgh.

• Captain Lionel “L-Train” Conacher scored Pittsburgh’s first-ever NHL goal.

• The last active Pirates player was Cliff Barton, who played his last NHL game in 1940.

• The Pirates colors of black and gold would be used as supporting evidence when the Pittsburgh Penguins switched to those colors in 1980.

• Four Pirates players would eventually be enshrined in the Hall of Fame:

– Lionel Conacher

– Frank Fredrickson

– Mickey MacKay

– Roy Worters

RELATED LINKS

• All-time Pirates roster and scoring

• Pirates goaltending, season by season

For speed, hard and accurate shooters and brains, the Pirates excel. There are no faster skaters in the circuit than Drury, McCurry, Milks, Darragh and Smith. Taking everything into consideration, the Pirates should be up near the top throughout the season.

PITTSBURGH PRESS, describing the Pirates before the start of their maiden season in the NHL

The NHL continues to inch south; Pittsburgh second U.S. team

PAUL CHRISTMAN

Pittsburghhockey.net Contributer

Pittsburgh’s first National Hockey League franchise got its start in 1925 when the growing NHL welcomed two new franchises – the New York Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates – and continued an incursion into the United States that began just the year before.

Pittsburgh’s first National Hockey League franchise got its start in 1925 when the growing NHL welcomed two new franchises – the New York Americans and Pittsburgh Pirates – and continued an incursion into the United States that began just the year before.

The NHL had started as an all-Canadian league with four teams in 1917: the Montreal Canadiens, Toronto Arenas, Ottawa Senators, and Montreal Wanderers. The Wanderers left the NHL when their arena burned down during that first season of 1917-18. And when Toronto suspended operations after the 1918-19 season started (following a Stanley Cup win in 1918), only Canadiens and Senators remained. Montreal defeated Ottawa in the 1919 NHL championship series and earned the right to play the Pacific Coast Hockey Association champion for the Stanley Cup (the Cup did not become a trophy that NHL teams exclusively played for until 1926). Montreal’s Cup series with the PCHA champion Seattle Metropolitans was suspended when the Spanish flu epidemic struck both teams. The flu took the life of Canadiens forward Joe Hall.

How the fledgling NHL withstood these and other storms and moved ahead is a fascinating story in itself. The entrance of the Quebec Bulldogs and Toronto St. Patricks brought the NHL back to four teams in 1919-20. The Bulldogs became the Hamilton Tigers after one losing season. The NHL came to the United States for the first time in 1924 with an expansion team, the Boston Bruins. At the same time, Montreal also received an expansion team, the Maroons, which created an intercity rivalry with the Canadiens. In 1925, the NHL entered New York, the largest U.S. city. The Hamilton Tigers players went on strike over not being paid extra money to play in the 1925 playoffs. Bootlegger Bill Dwyer then bought the rights to the Tiger players, moved the team to New York, and named it the Americans.

The NHL also expanded to Pittsburgh in 1925. The western Pennsylvania city already had every right to be proud of its hockey history. Pittsburgh’s entry into the NHL helped to forestall Eddie Livingstone, a controversial NHL nemesis, and his plans for a proposed rival league. Livingstone pushed for such leagues at various times from 1918 until the mid-1920s, but none materialized. In 1926, the NHL would add a second New York team, the Rangers, as well as the Chicago Blackhawks and Detroit Cougars (eventually the Red Wings). At that point, it was a 10-team league. The NHL’s inroads into the United States worried some established members of the league. In small-market Ottawa (population of 153,000 in the 1921 census), the league-leading Senators wondered how long their team would be able to compete successfully.

The newborn Pittsburgh NHL franchise had a long and honorable tradition to uphold. Pittsburgh had been the base of the Western Pennsylvania Hockey League and was home to the Schenley Park Casino, the first United States Olympic hockey team, the Duquesne Garden, and the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets, champions of the United States Amateur Hockey Association (USAHA) in 1924 and 1925. The owner of the Yellow Jackets was the respected Roy Schooley, whose hockey background extended back to 1901. Financial problems forced Schooley to sell the Jackets to Pittsburgh attorney James Callahan and Duquesne Garden president Henry Townsend. The USAHA soon folded, but most of the Jackets became members of the new NHL team, which Callahan and Townsend ran.

- Roy Schooley

Schooley was not done with hockey. NHL President Frank Calder said he wouldn’t be surprised to find Schooley being “the moving spirit” behind Livingstone’s push for a rival league. As the USAHA broke up, Calder reasoned that some of the cities that had lost amateur teams would push for their own professional squads, especially with the line between “amateur” and “professional” hockey said to be thin. Ralph Davis of the Pittsburgh Pressheld that the only difference between professional and amateur hockey apparently was that “the pros get their money openly and boast about it, and the amateurs take theirs under cover and are silent about it.” The differences didn’t quite end there. As the NHL Pirates prepared to play their first home game, the Pittsburgh Press noted that fans would see a different brand of hockey than they were used to with the amateur Yellow Jackets. “Petty” offsides would be eliminated, and forward passing and kicking the puck would be permitted in the 40-foot center ice area. The NHL game was also played in three 20-minute periods, versus the three 15-minute periods of amateur hockey. The Press alluded to any number of other innovations in the pro game and concluded that hockey would now be considerably faster and more interesting from every angle, recalling the days of the ˜pro’ sport here 25 years ago. A question remained: How well could amateur-turned-pro players make the adjustment?

If Calder needed an example of the push in certain cities for pro hockey, he had one in Pittsburgh. When Livingstone failed to launch his new league and the Yellow Jackets were sold to Townsend and Callahan, Schooley announced that another new professional hockey league would replace the USAHA. (See Morey Holzman and Joseph Nieforth, Deceptions and Doublecross: How the NHL Conquered Hockey (The Dundurn Group, 2002).) That league emerged as the Central Hockey Association in 1925 (later, the American Hockey Association (AHA) from 1926 to 1942). It operated in the upper Midwest, but not in Pittsburgh. Livingstone came in as owner of the AHA Chicago Cardinals in 1926-27. Schooley was not directly associated with the new league. He instead stayed active in Pittsburgh politics. But he re-entered hockey with the West Penn Amateur League in 1928-29 and the Pittsburgh Yellow Jackets of the International Hockey League in 1930.

A new league, team name, and coach – and familiar players

Pittsburgh’s new NHL team had new management (Callahan and Townsend), but there were no substantial changes in the player roster from the year before. Almost all of the previous year’s champion Yellow Jackets signed on with the new NHL squad. Trading their yellow and black Jackets uniforms in for the Pirate yellow and black were goaltender Roy “Shrimp” Worters, defensemen Lionel Conacher, Herb Drury, and Rodger Smith, and forwards Harold “Baldy” Cotton, Harold Darragh, Francis “Duke” McCurry, Hib Milks, and Wilford “Tex” White. Two of these players (Conacher and Worters) would become Hockey Hall of Fame members. Conacher was nicknamed “The Big Train” and voted Canada’s top athlete of the first half of the 20th century. He was the acknowledged leader of the Jackets, and he helped recruit friends like Worters, Darragh, and Cotton for the team. Conacher’s value to the Pirates was clear when the team signed him to a three-year contract at a record salary of $7,500 per year. Worters’s acrobatics made him one of the top goaltenders of his era. The 5’3″ Worters was the first NHL goalie to record back-to-back shutouts. He played in virtually every Pirates game in their first three years, during which Pittsburgh made the playoffs twice.

The former Yellow Jacket players would not play under the watch of their former behind-the-bench leader. Dick Carroll was the coach of the Jackets in their championship years of 1924 and 1925. He had guided Toronto Arenas to the Stanley Cup in the NHL’s inaugural year of 1917-18. The Arenas were the first NHL team to win the Cup in that pre-1926 era when the NHL did not exclusively control the trophy. Carroll’s Toronto Canoe Club team took the Memorial Cup in 1920. He then came to Pittsburgh to coach the Jackets. Carroll was a very close associate of Eddie Livingstone, that thorn in the NHL’s side. Not surprisingly, Carroll did not switch to the NHL in 1925 but instead accompanied Livingstone to the AHA in 1926. Carroll began a very successful five-year term as coach of the Duluth Hornets and next the Tulsa Oilers. He had less success later when he coached the AHA St. Louis Flyers and Oklahoma City Warriors.

In mid-October 1925, the Pittsburgh NHL franchise named 33-year-old James Ogilvie “Odie” Cleghorn as its coach. A fancy dresser off the ice, Cleghorn was a right-winger with a reputation as a fine stick-handler who could come back and play with finesse on defense. He was younger brother of Hall of Fame defenseman Sprague Cleghorn, then with the Bruins. Odie had played for the New York Wanderers, Renfrew Creamery Kings, Montreal Wanderers, and Montreal Canadiens since the 1909-10 season.

As the 1925-26 season approached, the Ottawa Senators objected to Pittsburgh’s entry into the NHL. Ottawa’s primary concern quite possibly was its own ability to keep up with new NHL teams entering larger U.S. markets. However, the Senators’ stated claim was that two-thirds of the Pittsburghers were players who had skated as amateurs the previous year in the USAHA and thus would not compete equally with the players of other NHL teams. Whether “amateur” USAHA players could make the grade in the NHL was debated. But it was worth noting that these former Yellow Jackets were experienced. Their hockey careers had started between 1914 and 1919, and they averaged 25 years of age. Two players were 29. And they had been paid in the USAHA, even if it was “under cover.” Frank Calder called amateur hockey “a farce as regards amateurism.” Ottawa must have realized that they weren’t going to convert many other NHL teams to their position, given the facts about “amateur” hockey and the NHL’s thrust into the United States. At the NHL meeting of November 7, 1925, the Senators withdrew their objection to admitting Pittsburgh. The vote of the Board of Governors to let Pittsburgh in was thus made unanimous. The NHL now had seven teams.As Pittsburgh’s coach, Cleghorn was the first in the NHL to change his players on the fly, rather than when play stopped. He was also the first coach to use three set forward lines at a time when it was common to play the best players to their absolute limit and substitute on an irregular basis. Cleghorn’s first line had McCurry at left wing, Milks at center, and Darragh at right wing. The three would be spelled about halfway through the period by Cotton or Louis Berlinguette (left wing), Drury (center), and White (right wing). After the second line played six or eight minutes, the first line might reappear. Cleghorn could also use a third line. Fred Lowrey, Alf Skinner, and, in 17 games, Cleghorn himself played as substitute forwards (Cleghorn at right wing). The practice of using set lines was quickly copied by all NHL teams. Harland Rohm of the Chicago Tribune pointed out that this system had “the great advantage of having centers and wings work with men to whose idiosyncracies of play they were accustomed.”

But the new NHL team needed a name. It is said that Callahan named his club “Pirates” after he cashed in a favor from Barney Dreyfuss, the owner of the baseball Pittsburgh Pirates of nearby Forbes Field. Details of this favor are not known, but Dreyfuss apparently came through for Callahan quickly. The Pittsburgh Press referred to the squad as the “Pirates” rather than the “Pittsburgh hockey club” for the first time November 11, when the team was four days old. Acquiring that name meant the NHL team had yet another honor to uphold. The baseball Pirates had used the Pirates name since 1891. They had recently defeated the Washington Senators in the 1925 World Series and added yet another Pittsburgh championship to those of the 1924 and 1925 hockey Yellow Jackets. Inevitably, Pittsburgh sports fans would likely expect much of the new hockey Pirates.

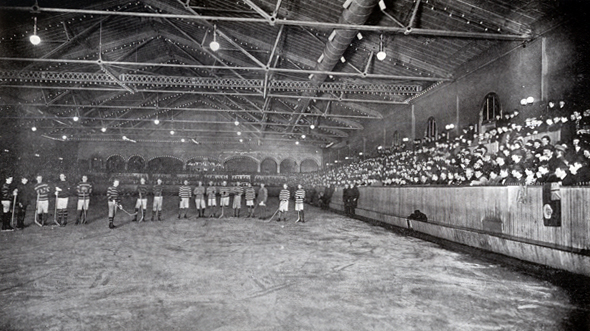

- Duquesne Garden, January 1900

Home ice for the Pirates, as it was for the Yellow Jackets, would be the Duquesne Garden, just north of the corner of Fifth Avenue and Craig Street in Pittsburgh’s Oakland section (near the site of the Schenley Park Casino, which had burned down in 1896). The Garden was first erected as a trolley barn in 1890. Six years later, it was converted into an arena seating about 5,000.

The Garden earned much praise in its early days. In the hockey encyclopedia Total Hockey (Andrews McMeel Publishing, 1998), Brian McFarlane related in Our Electrifying Game: Hockey in the Era of Gaslight the report of the manager of a Kingston, Ontario team that had journeyed to the Garden in 1902. The manager told the Toronto Globe, “Pittsburgh is hockey crazy. Over 10,000 turned out for our three games there. The fans paid 35 cents for general admission and 75 cents for a box seat. The manager said that receipts came to a total of $4,000, but all we got for our share was about $350, which, after expenses, will leave about enough to buy some postage stamps. Yet, the manager reported, the Pittsburgh rink is a dream . . . The place is lighted by thousands of incandescent lamps. The band is always in attendance and there is every convenience for patrons. What a marvelous place it is.”

By the 1920s, however, the place could hardly be more outdated. The Garden was not up to the occasion of Pittsburgh’s entrance into the NHL. New rinks were springing up in almost every other city in the league. About 15,000 fans could be comfortably seated in New York, Boston, and Montreal. Not even half that number could squeeze into the Duquesne Garden.

Moreover, the ice-making operation at the Garden was quite antiquated. On Monday, October 12, 1925, as the Garden’s opening for public skating approached, the Pittsburgh Press reported, “Experts today began freezing the ice at Duquesne Garden for the grand opening Friday night.” The Friday referred to, of course, was four days away. Rinks built in the 1920s could produce an adequate ice surface in four hours, according to a 1931 Press story. In November 1927, the Toronto Star reported that the Pirates had to train at a local gym instead of the Garden. The Garden’s ice machine had broken down. The ancient arena would always severely hinder the Pirates.

But as the NHL was about to debut in Pittsburgh, local sportswriters tended to ignore the Garden’s many defects. They were more inclined to eagerly pump up the Pirates’ chances in big-time hockey. The Garden, they said, would have trouble holding the expected crowds. On November 12, 1925, just five days after the Pittsburgh entered the NHL, the Pittsburgh Press predicted that the Pirates should be as strong as any NHL team, with the possible exception of the New York Americans. The Press stated, “For speed, hard and accurate shooters and brains, the Pirates excel. There are no faster skaters in the circuit than Drury, McCurry, Milks, Darragh and Smith. Taking everything into consideration, the Pirates should be up near the top throughout the season.” If the Pirates were to finish in the top half of the standings, the Press said, it would be “quite an achievement the first year in fast company.”